In the

Steps of Christopher Columbus

& Sir Walter Raleigh,

who both explored

the Orinoco delta.

The Macareo River is one of the main rivers in the delta of the Orinoco. It is only 20 NM from the South coast of Trinidad but seems to be not much visited by yachts.

The main reason to visit this river is to meet the Wareo Indians, the small friendly people who live along the river bank. It is only a matter of time before they will be forced to change their way of life and conform to more "civilised" living. At the village about ten miles upriver there is a small school and a health clinic run by the Venezuelan government. As a result, some humbler settlements further upstream have been abandoned as the inhabitants have moved to be near the school and clinic.

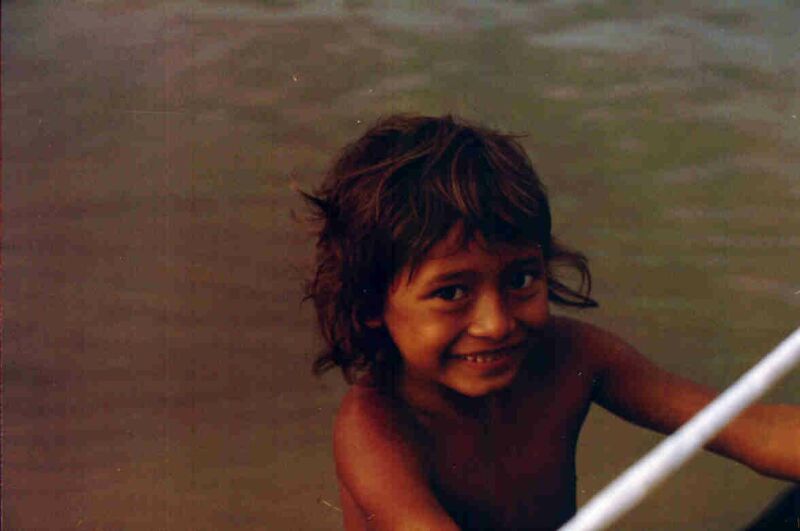

A Wareo child

In company with two other yachts we left the Chaguaramas anchorage for Columbus Bay, just North of Icacos Point,

on the SW corner of Trinidad.

The following day we left early, heading for the mouth of the Macareo River. The entrance is at least two miles wide with a featureless approach. The West bank is not visible and the area off it is marked "unsurveyed" on the chart. There is no trace of the marker stakes shown on the

American DMA charts. We followed along the Eastern shore which is low and lined by tall trees. I believe the least depth at Low Water is about 2m or maybe less in places. The bar goes on for a long way and I feel we were lucky not to touch the bottom here. Once inside the depth nearly everywhere is over 5m and as much as 20m.

Apart from waking at 0100 am from mosquito attacks, easily cured by repellent and mossie coils we had a quiet night, though the mosquitoes by night and the stinging flies by day became a real nuisance the further up the river we went.

Torpedo particularly did not like the biting insects. Our amateur efforts at fixing mosquito netting to the hatches and companionways were just not up to it! We were woken at 0600 when we heard a strange noise followed by a violent swing. We were in the grip of the current and watched as we performed a 360 degree turn. At all times the current flowed strongly, usually at three knots and sometimes more.

Very many Scarlet Ibis birds have taken to perching in the branches of the mangrove trees lining both sides of the river. We also saw macaws (always flying in pairs) and many other birds including large brown turkey-like birds - we are not ornithologists! There is no river bank as such, just tall mangroves and even taller trees and what must be semi-aquatic palms. Every so often mysterious channels branch off into the depths of the forest, giving glimpses of yet more water plants. A silent procession of water hyacinth and saw grass clumps, some of which are large islands, glide down the river unceasingly. Once we were quite sure we saw a dead anaconda floating by, at least ten feet long.

On our second morning in the river we were amazed to see a white-hulled sports fisherman flying the Red Ensign cruising downstream. The skipper turned out to be Jim of "Gato del Mar". He was on his way from Brazil to Trinidad, but had entered the main Orinoco and steamed upstream to the confluence of the Macareo. He was equally astonished to see three British yachts at anchor! Later he turned upstream leading the way to a backwater he had passed earlier, and after anchoring invited us on board for an impromptu evening party. (No, we were not wearing dinner jackets in the jungle!).

The Wareos live in thatched huts on stilts, almost in the water and mostly open fronted, so one can look straight into their living room. They have little or no furniture, their belongings are stowed in bags hanging from the rafters. Under this and above the water level is another storage space where they keep their dugout canoes. Walkways connect all the huts, while dogs roam the mud beneath.

They are small folk, living on and in the river. "Wareo" means canoe people and both sexes of all ages are expert handlers of their light but leaky dugouts. There are usually two paddlers in each; passengers are expected to keep bailing. Many canoes are handled by quite young children who have a hard time paddling back upstream. One of our party proved to be an excellent canoe paddler and handled a paddle with aplomb. He was nearly as good as the tiny paddler in front of him who lay back and let him do all the work! We couldn't help noticing many young people are lacking teeth, maybe caused by their diet. We were told the river water is badly polluted from the towns and settlements many miles upstream. The doctor at the clinic tries to advise them to boil their water, but they consider what wood is available is too precious to use for this purpose. During the rainy season at least they have no other source of water but the river.

For trading with the Indians we took goods such as toys for the children and foodstuffs such as flour sugar and powdered milk for exchanging for woven baskets of many sizes, necklaces made from beads and coins, canoe paddles and model boats. It is amazing what you can do with sign language and supermarket Spanish! However nobody wanted fish hooks for example. What we were constantly asked for was two metre lengths of cloth and "flanella" (T-shirts). We only had our own and these were rejected if slightly "holey"! The ladies particularly wanted hair shampoo, "colognia", and nail varnish. They were not particularly interested in the supplies of flour, sugar and powdered milk we had brought, although these were welcome the further up we went.

On our way downstream a canoe came paddling furiously towards us. It contained a husband and wife who were very keen to trade with us. We slowed right down and they came alongside, climbed on board and tied up (much to our amazement!). They had beads and necklaces with them but we already had these. After some fifteen minutes we heard an agitated "squeaking" sound coming from them both. They were pointing astern and to our horror we saw that their little dugout canoe had come loose and was rapidly disappearing in the current.

As we had no wish to arrive back in Trinidad with two displaced Indians, we hurriedly turned round and caught up the errant canoe. They were extremely happy to be reunited with their major possession and soon were on their way from whence they came.

The aspect of the river changed hardly at all as we continued slowly upstream, just mile after mile of verdant green growth lining both margins. There was supposed to be a path leading to a savannah, but we never found it.

In the evenings we tried to anchor clear of the main stream in a creek or backwater. The hush was impressive, only bird noises and sometimes the rustle of some vegetation passing by. Dinghy trips up the side channels in the evenings were very popular, gliding silently with the current until further progress was no longer possible, then turning round back for a welcome glass or two of wine.

In a backwater

In the side streams where we anchored we would see and hear many pink dolphins which were not affected by our presence. In fact they seemed to like to be near the anchored yachts. They would startle us with loud exhalations and other strange and humorous noises. They are quite unlike the sea dolphins we know and love. They are more pinky-grey than pink, with strange snouts looking like medieval armour.

We did not see other land animals, although howler monkeys were highly audible. They made a terrific racket at times, more of a growl than a howl! Sometimes in the evening something would move silently from the grass into the water, maybe they were caimans?

As we lay at anchor again in Columbus Bay at the end of our expedition, having successfully negotiated the shallow river mouth, we agreed that it had been a truly absorbing and fascinating experience. We shall particularly long remember the happy natural smiles of the children standing in their canoes, their faces lining the toerail as they looked over the top at us.

![]()